Qaanaaq March-April 2022: Surveying The Ocean Under The Ice

by Steffen M. Olsen | Published: 08-Apr-22 | Last updated: 08-Apr-22 | Tags : Arctic biodiversity Greenland ice indigenous | category: NEWS

The Danish Meteorological Institute's Steffen M. Olsen sent us an update from Qaanaaq, where he is doing fieldwork for Arctic PASSION's community-based management work on Arctic marine climate change, noise pollution and impacts on marine living resources.

The community in Qaanaaq rely on hunting and fishing on the Inglefield fjord during summer and winter. The nearby Pikialasorsuaq (North Water Polynya) has been defining both human cultures and the biodiversity and biological productivity in the area for thousands of years. The fate, cycles of Pikialasorsuaq and associated available open water area that is central to species and Greenlanders is central to the region.

In winter the fjord is typically covered with meter thick land fast ice from December into June, where long line fishing for halibut is the primary activity. When summer approaches and the ice edge moves closer in, hunting for walrus, seal and in particular, narwhal becomes the dominating activity. During recent years the winter catch of halibut has been steadily increasing, but also the fishing to has moved further into the fjord where a number of calving glaciers dominates the scenery generating massive icebergs and mélange. Here the warm waters from the deep with origins in the Atlantic (Gulf Stream), interacts with glaciers and ice causing mixing and upwelling from depth. These processes, drivers of Pikialasorsuaq, limit sea-ice growth but also bring nutrients from depth into the euphotic zone where they form the basis for a productive local ecosystem on which also migrating species like narwhal and beluga rely.

We know that these favorable conditions may vary, for example, when ocean stratification limits the upwelling, but we still have limited understanding on how climate change and natural variability in the physical ocean environment affects the ecosystem and livelihood of the local community. Within Arctic Passion we engage with the local community of Qaanaaq to collect combined data and knowledge on the marine environment and the presence of marine mammals through underwater recording of their voices. The ambitious goal is to empower the community to monitor and understand their environment, as a tool for sustainable use of resources and adaptation to climate change and climate variability.

A collaborative full fjord survey of ocean and ice conditions has been ongoing for the last week by a team of local hunters and scientists. We use of dog sleds, which is still the superior form of transport in areas of rough ice conditions. Local knowledge and traditions are critical for a safe and successful program, designed to meet both scientific and local needs through initial dialogues between the local and scientific team members.

Later in the ice season we will collaboratively deploy ‘sound traps’ from the ice, instruments that will stay over summer and record the entry to the fjord of vocal marine mammals as the sea ice retreat for the short summer season, but also the noise in the marine environment generated by natural and human activities. Noise pollution is of great concern to the community and Arctic Passion will build the first baseline dataset from the region of the marine soundscape.

Inglefiled Fjord is about 100km long, from the ice edge to the North Water to the calving glaciers at the head of the fjord. Travelling with sleds to monitor ocean and ice conditions takes some time. Camping on sleds with reindeer and musk oxen skins to sleep on. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

Inglefiled Fjord is about 100km long, from the ice edge to the North Water to the calving glaciers at the head of the fjord. Travelling with sleds to monitor ocean and ice conditions takes some time. Camping on sleds with reindeer and musk oxen skins to sleep on. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

Dog sleds are superior in order to navigate the icescape. Also in early summer when ice breaks up, the long sleds can cross the leads forming in the sea ice. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

Dog sleds are superior in order to navigate the icescape. Also in early summer when ice breaks up, the long sleds can cross the leads forming in the sea ice. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

Waking up to more snow. The region is relatively dry and snowfall limited. New snow slows down the sled teams. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

Waking up to more snow. The region is relatively dry and snowfall limited. New snow slows down the sled teams. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

When conditions are good, work often continues into the late evening

hours or as long as light is available. Here a CTD (oceanography) being

operated to measure ocean temperature and layering of warm, cold, more fresh

and salty waters. Depths exceed 900m, with the heat stored at 300m depth, which

is also the preferred depths for halibut fishing. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

When conditions are good, work often continues into the late evening

hours or as long as light is available. Here a CTD (oceanography) being

operated to measure ocean temperature and layering of warm, cold, more fresh

and salty waters. Depths exceed 900m, with the heat stored at 300m depth, which

is also the preferred depths for halibut fishing. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

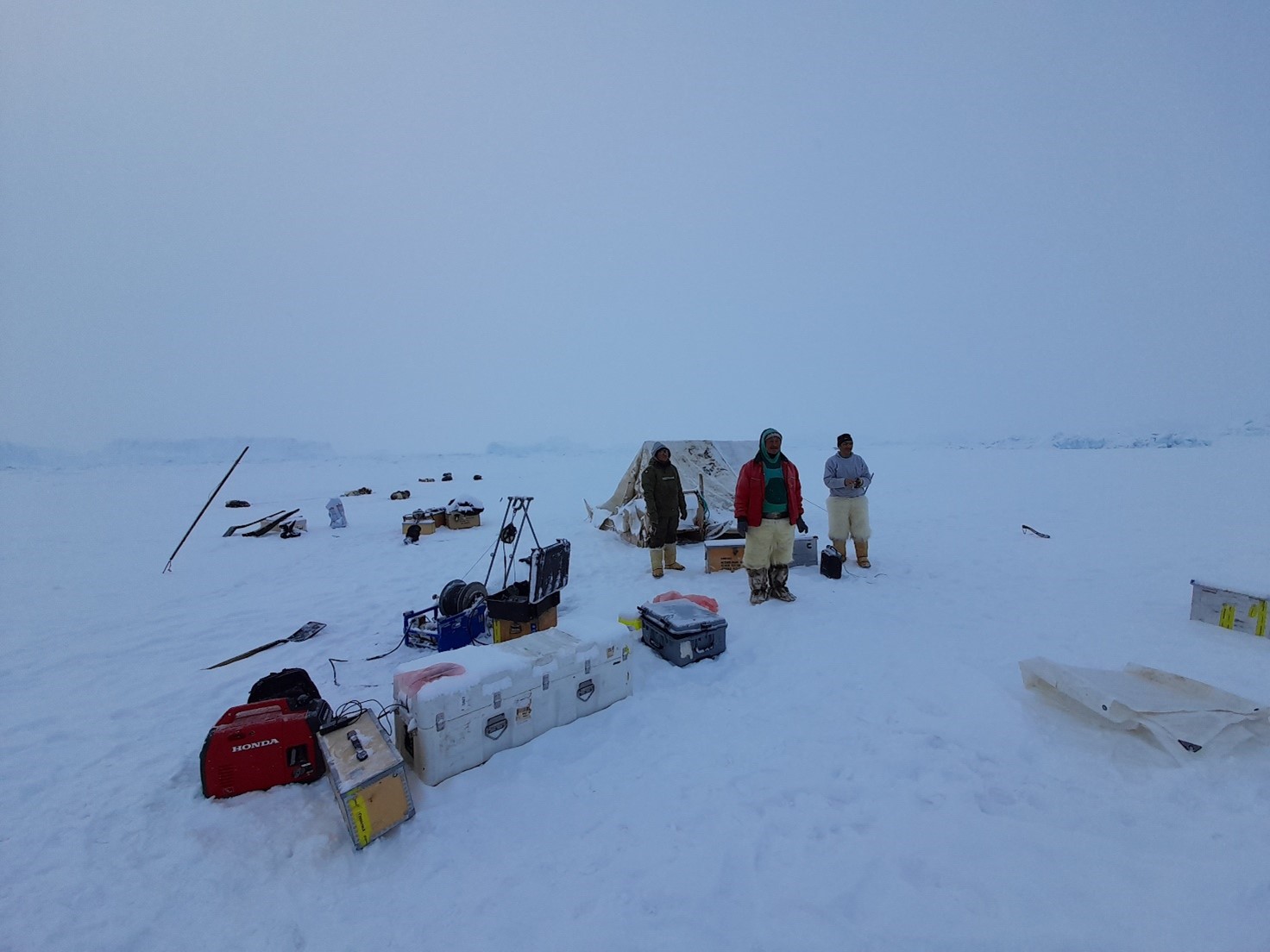

The team from Qaanaaq, Qidtlaq Danielsen, Gustav Simigaq og Gedion Kristiansen. Qidtlaq,

Gedion and Gustav are all full-time hunters from the Qaanaaq region. Qidtlaq

acts as anchor person setting the team and leading the trips on the ice. We

have a long established relation with the families and a excited to see how

also the new generation, Gustav, is now joining in with own sled and dog team. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

The team from Qaanaaq, Qidtlaq Danielsen, Gustav Simigaq og Gedion Kristiansen. Qidtlaq,

Gedion and Gustav are all full-time hunters from the Qaanaaq region. Qidtlaq

acts as anchor person setting the team and leading the trips on the ice. We

have a long established relation with the families and a excited to see how

also the new generation, Gustav, is now joining in with own sled and dog team. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

When it gets cold, traditional clothing is superior/preferred. Anonymous / Qidtlaq Danielsen. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

When it gets cold, traditional clothing is superior/preferred. Anonymous / Qidtlaq Danielsen. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

Lenticular clouds forming, can be a sign of upper winds breaking through to the surface but also very beautiful. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen

Lenticular clouds forming, can be a sign of upper winds breaking through to the surface but also very beautiful. Photo: Steffen M. Olsen