Using Oral Histories, Indigenous Knowledge And Local Knowledge For Monitoring Environmental Change In Canada

by Sabrina Heerema with contributions from Leslie McCartney and The Gwich’in Tribal Council Department of Culture and Heritage. | Published: 28-Feb-22 | Last updated: 28-Feb-22 | Tags : Arctic environment indigenous observation | category: NEWS

The Arctic PASSION project attempts to address what needs to be done to improve and extend terrestrial, marine and cryospheric measurements and community-based monitoring systems; What services and networks are necessary for adaptation to climate change in regions; What is the best way to involve Indigenous Peoples, local populations and other actors in the region in the co-creation of useful services; How an operational observing system can build on the essential contribution of Indigenous Knowledge and Community-based Monitoring (CBM) systems; How we can help to integrate Community-based observations, Traditional Knowledge and scientific observations into an integrated Sustainable Arctic Observing System; The societal benefits of an observing system for people(s) living in the region as well as those living outside of the Arctic domain; How ro support communication between scientists, policy-makers, commercial actors and local population.

The project will work on answering these questions through co-creation of the solutions together with indigenous and local communities, and the ‘Event Database of CBM using Oral Histories, Indigenous Knowledge and Local Knowledge’ will fill key data gaps through co-creation of consented knowledge on environmental change: using oral and other historical accounts to reconstruct key events with the consent of those providing the accounts.

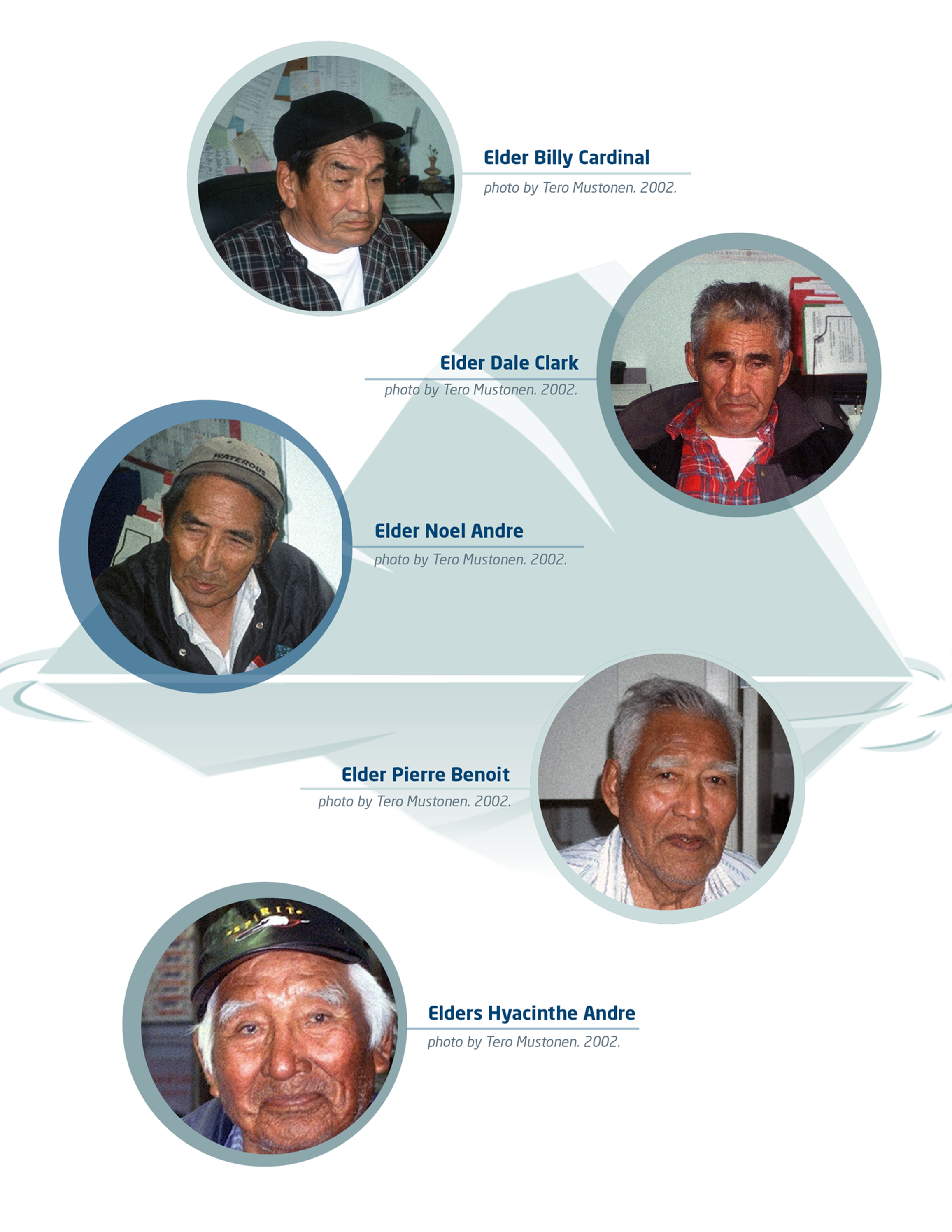

Tero Mustonen, who is the chairperson of the Snowchange Cooperative and together with Malene Simon from the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, is leading Arctic PASSION’s work on innovating user-driven Arctic pilot services, is working on the co-creation of consented knowledge on environmental change in seven regions: Alaska (USA), British Columbia/Yukon/Northwest Territories (Canada), Western Greenland, Northern Finland/Norway, Murmansk (Russia), Khanty-Mansia (Russia) and Sakha-Yakutia (Russia). Tero has had contact with Gwich’in communities since 2000 and worked with the community of Tsiigehtchic for a large oral history documentation project in 2002-2003. He has created a method for assessing Indigenous and Local Knowledge through oral histories and sorting them by year in a database. The specific Gwich’in database contains high-quality socio-ecologically relevant events focusing on ecosystem changes of significance dating from 1972 until now, although the narratives in the database refer as far back as the 1840s, which will be useful to match with historical data to gain greatest perspective. In addition, accounts of environmental change in the time period before scientific observations were made could be helpful. The database covers British Columbia, Yukon and the Northwest Territories in Canada.

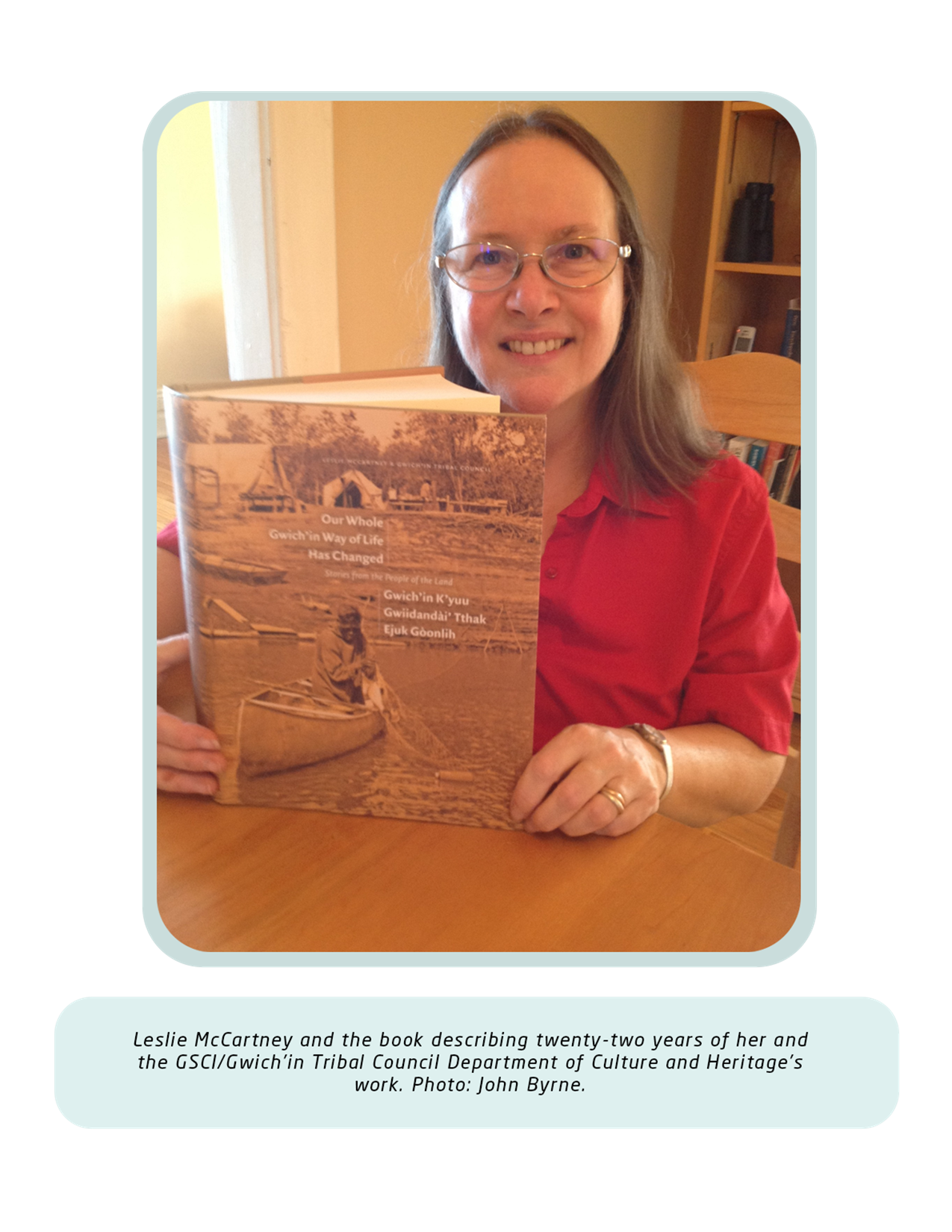

To bring the Gwich’in Tribal Council Department of Culture and Heritage on board with this project, Tero has enlisted the help of Leslie McCartney, Anthropologist, Assistant Professor and Curator of the Oral History Collection at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Leslie has worked in the oral history field for over twenty-two years in places such as the Canadian subarctic, Alaska, England and Ireland.

She lived in Tsiigehtshik for three years in the early 2000s and has worked with the Gwich’in since 1998 when the Gwich’in Social and Cultural Institute (GSCI)[1] asked McCartney—who was then a postgraduate (and mature student) at Trent University in Ontario, Canada, working on her master’s degree in cultural anthropology—to be the project coordinator in the Gwich'in Elders’ Biographies Research Project, a project to record the life stories of Gwich'in Elders.

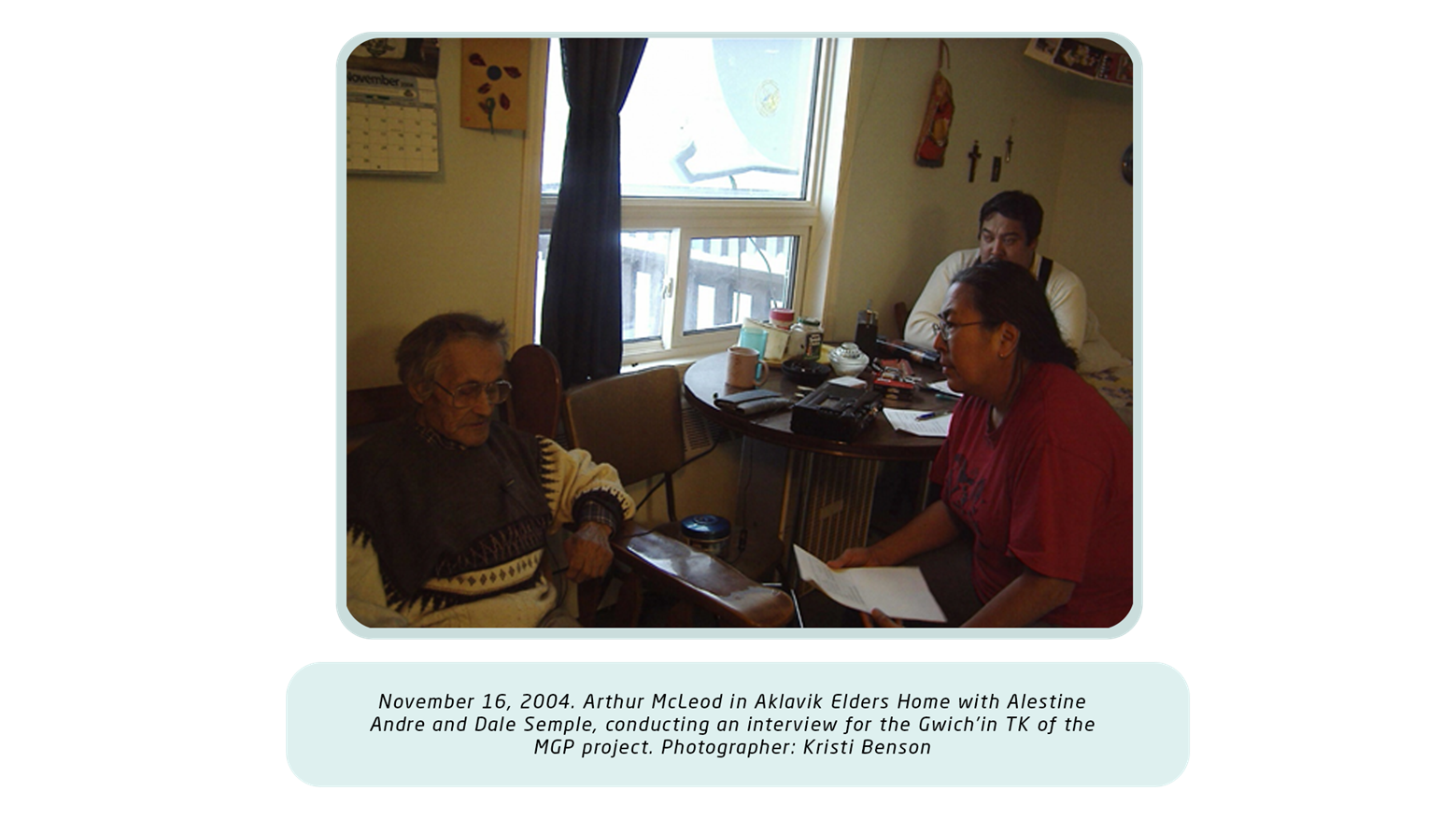

She was asked to interview and record the stories twenty-three of the oldest Elders in the four NWT Gwich’in communities (Fort McPherson, Aklavik, Inuvik, and Tsiigehtchic). Most of the Elders interviewed are members of the last generation to fluently speak Dinjii Zhu’ Ginjik, the Gwich’in language, as their mother tongue. Dinjii Zhu’ Ginjik is one of the most endangered Indigenous languages in Canada and it is the most endangered Dene (Athapaskan) language in the Northwest Territories.[2]

In December 2021 Leslie and the Gwich’in Tribal Council released a book about the life stories and experiences of the Gwich’in Elders (twenty-two years in the making) entitled “Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed / Gwich’in K’yuu Gwiidandài’ Tthak Ejuk Gòonlih Stories from the People of the Land”. It was published by University of Alberta Press and winner of 2021 Oral History Association's Book Award for outstanding use of oral history, and it has received coverage in the national Canadian news here.

This was just one of many projects the GSCI, now Gwich’in Tribal Council Department of Culture and Heritage has completed. Since it’s founding in 1992, the GSCI has been involved, sometimes with outside researchers, in more than 120 projects, many if not all have involved community members and Elders. Many of these projects involved researching place names on the land, recording an inventory of heritage sites, recording and sharing Traditional Knowledge, and traditional land use studies all using oral history and ethno-archaeology. The geo-spatial toponymic information gathered over this twenty-five-year period of time has been synthesized down into one map, the Gwich’in Place Names Atlas, an interactive cybercartographic map.[3] Dozens of reports are also available on the Department’s website.[4]

The land is central to the Elders’ narratives. Because the Gwich’in ‘live off the land’ through seasonal access of the resources that land and water provide, the Elders’ stories often mention the names of places they travelled to and lived on. While some place names describe geographical features; others are related to the resources that can be found there.[5] Many said that when talking about the land, they wanted to speak in Gwich’in because their language was more descriptive and they could discuss the land better in their own language.[6] Land is so integral to the Gwich’in lifestyle that the various band names reflect the landscape on which they lived. For example, Gwichya Gwich’in literally means “people of the flat lands” (Gwichya = “flat land”; Gwich’in = “people”). This name is given to the people who live in the Mackenzie River area where the land is flat. The name refers to the entire lowland region around the confluence of Tsiigehnjik and Nagwichoonjik (Arctic Red River and Mackenzie River). The people living around the Fort McPherson area call themselves the Teetł’it Gwich’in. Teetł’it refers to the headwaters of Teetł’it Gwinjik (the Peel River), their traditional homeland prior to the arrival of the fur trade.[7]

Thousands of pages of transcripts from all of these combined projects exist in the Gwich’in Tribal Council’s archival holdings. Over the course of the next three years Leslie will be reviewing publications and transcripts of Indigenous Knowledge observations from Gwich’in Tribal Council’s archive, looking for indicators of change. Changes documented include seismic activity in the 1960s and more focus on ice conditions in the 2000s. The descriptive text that Leslie is searching for includes examples such as ‘a long time ago’.

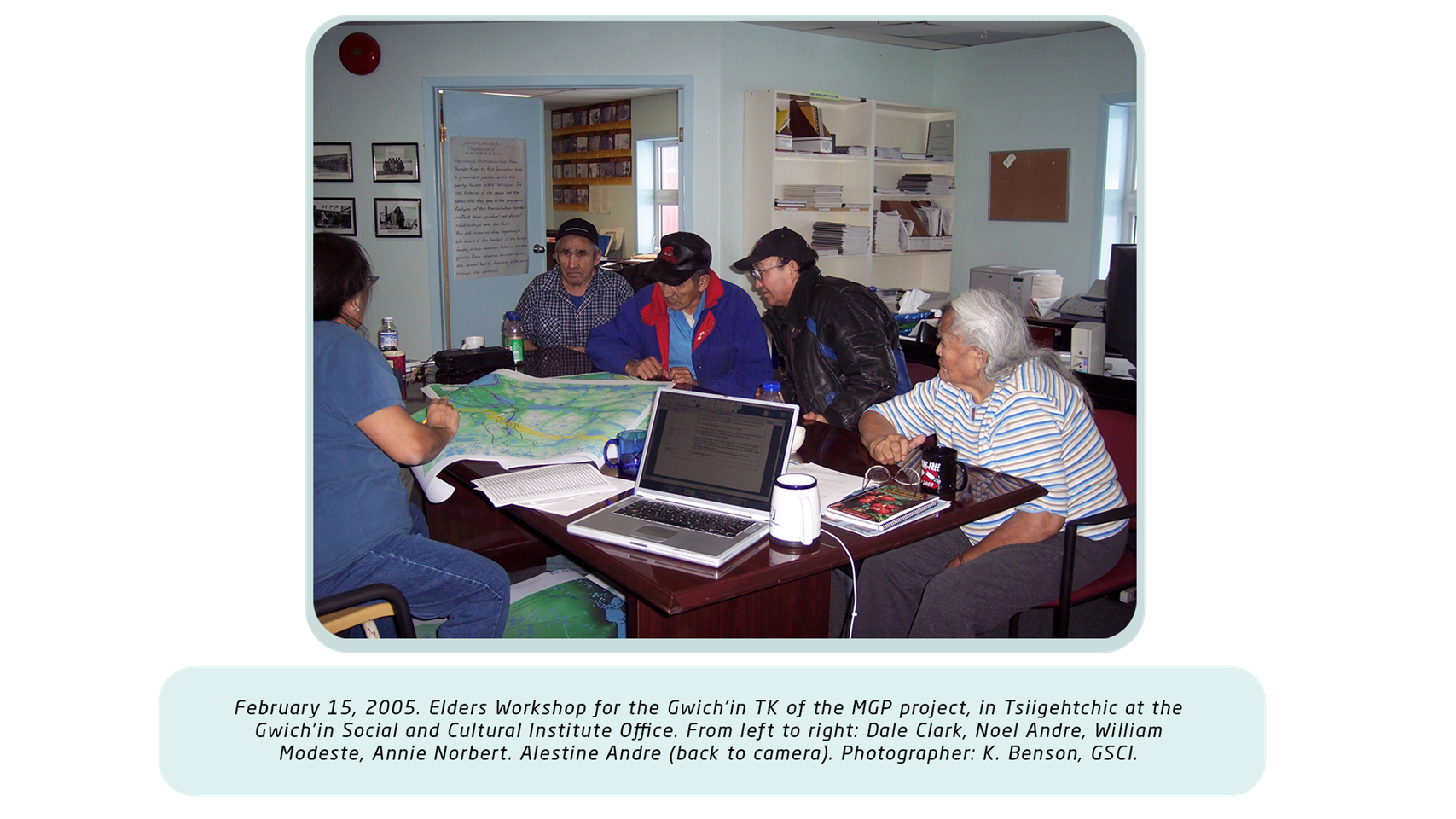

The first transcripts that Leslie will review are from two events occurring along the Mackenzie River. The Mackenzie River, which is known as Nagwichoonjik in the Gwich’in Settlement Area, is the longest river system in Canada, flowing northwest from Great Slave Lake into the Arctic Ocean, where it forms a large delta at its mouth. The Gwich'in Traditional Knowledge Study of the Mackenzie Gas Project Area was initiated in response to regulatory requirements under various environmental assessment acts/policies for the inclusion of traditional knowledge and environmental impact statements for the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Project (2000/2001). This was one of the GSCI’s largest projects and had a focus on the land. The transcripts include observations about changes to the land along the proposed pipeline route, from people with intimate ties to the land. The changes noted include such things as erosion, permafrost thawing, flooding or a warming climate. During the process the interviewees discussed Gwich’in land use and although it was not the focus of the project, environmental changes became part of the discussion as the Gwich’in view their lands and experiences holistically. After looking at the transcripts from these projects, Leslie will move on to examine the transcripts and reports from the GSCI/GTC’s other projects, of which there are thousands.

The Department of Culture and Heritage of the Gwich’in Tribal Council has worked with Gwich’in communities in Northwest Territories since the early 1990s to record the Elders, and Snowchange has been working with the Indigenous communities of the Tahltan First Nations people in British Columbia and Yukon since the early 2000s to record Elders discussing changes in the environment. Tero and Leslie are working together to link the work the Tahltan have been doing with Snowchange and the work the Department of Culture and Heritage have done for a more comprehensive picture of environmental change across the Canadian north.

In this work, Tero, Leslie and the GTC Department of Culture and Heritage can observe the similar ways of producing knowledge and compare discoveries on how erosion, climate change, etc. contribute to how the land and rivers in the Gwich’in Settlement Area are changing. Leslie and Tero will be reviewing existing materials on how the environment has been changing. The end report will help communicate their findings to scientists. All of the research in Indigenous communities has to be licensed by the Aurora Research Institute and approved by the communities, thus, the communities are invited to comment on the research. Something has to be given back to the community, and this way of working is common in northern Canada. Indigenous knowledge is not just a checkbox, it’s not like that in the Northwest Territories, it is integrated into the science. The value of Indigenous knowledge is not just in the data gathered, it is also the insight gained on how Indigenous people survey the land and space.

Indigenous knowledge is not just a checkbox, it’s not like that in the Northwest Territories, it is integrated into the science.

Through reading Indigenous oral histories, it is possible to learn more about the place names, history and culture of the Gwich’in. Elders play crucial roles as teachers of traditional knowledge, history, language, and culture; a way of life based on a special spiritual relationship between the Gwich’in and the land; the preservation and respect for the land as essential to the well-being and subsistence lifestyle of the Gwich’in people and their culture.[8] Through this cooperation with the Gwich’in we also hope to increase respect and understanding of the culture. While scientific data is regarded as authoritative, Indigenous knowledge can be viewed as an alternative, less-reliable source and there is scepticism about its usefulness. However, Indigenous and local knowledge is accurate knowledge that has been preserved and passed down through generations, and not only through generations but since the world was created. As the first item in the preamble of the Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement acknowledges, “the Gwich’in have traditionally used and occupied lands in the Northwest Territories and in the Yukon from time immemorial.” [9] In addition to supplementing gaps in scientific knowledge, oral history (stories) are ways of talking about the past and hearing voices that have been, to date, marginalized.[10]

Oral history (stories) are ways of talking about the past and hearing voices that have been, to date, marginalized.

Leslie and Snowchange have a first baseline structure for organizing the observations ready and by summer the first results will be made available. Leslie and the Gwich’in Tribal Council will publish the conclusions of their findings in a report, in December 2024. While this is just the beginning of Arctic PASSION’s cooperation with the Gwich’in Nation, we hope to catch up with Leslie again in 6-8 months when more results will be available.

Endnotes

[1] The Gwich’in Tribal Council (GTC) was originally established to negotiate the Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement, and then following its signing, to implement it. The GTC then established several organizations to deal with the responsibilities created under the agreement. The Gwich’in Social and Cultural Institute (GSCI) was founded as the cultural and heritage arm of the Gwich’in Tribal Council in response to Gwich’in concerns about the decline of Gwich’in culture and language. The GSCI was also charged with implementing the heritage resource responsibilities set out in the Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement, which included providing a record of Gwich’in use and occupancy of the settlement region through time by way of place names, archaeological and historical places, sites, and burial sites, through artefacts and objects of historical, cultural, or religious significance and any other type of records, as well as involvement in the conservation and management of these heritage resources. In the autumn of 1993, the GSCI commenced work with a mandate to “document, preserve and promote the practice of Gwich’in culture, language, traditional knowledge and values.” The GSCI became integrated into the Gwich’in Tribal Council as their Department of Culture and Heritage on April 1, 2016.

[2] Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed, xxii

[3] Gwich’in Place Names Atlas, https://altas.gwich’in.ca

[4] www.gwichin.ca

[5] Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed, xvii

[6] Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed, xxiv

[7] Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed, xxx

[8] Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed, xv

[9] Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed, xxx

[10] Our Whole Gwich’in Way of Life Has Changed, xxvi